——✿——

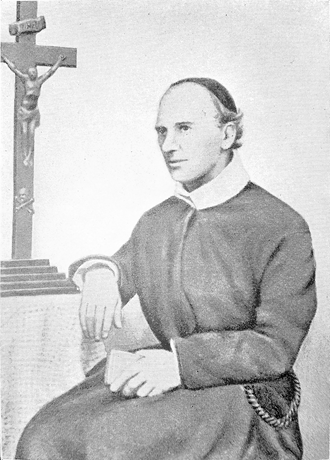

Early Years of Father Furniss,

until he was

ordained Priest.—(1809-1834.)

he late Canon Frith, in answer to a letter which I wrote

asking him for some information respecting the early life of Father Furniss,

says:

"I have known good Father Furniss since he was a little boy. He was born

June 19, 1809, in the neighbourhood of Sheffield, of which town I am also a

native. His father—a member of a respectable Derbyshire Catholic family long

settled near Hathersage—was a wealthy master-cutler, and resided at Bellevue, a

beautiful villa near Sheffield. His mother's name was Curr, sister to the Rev.

Joseph Curr, for many years priest at St. Mary's, Mulberry Street, Manchester. He

was a learned man, and wrote several works of a polemical character, in answer

to the clerical bigots of the day. He also published a translation of

Bourdaloue's Spiritual Retreat, and

of St. Alphonsus' Visits to the Blessed

Sacrament."

Father John Furniss had two brothers,

Albert and Bernard, and one sister, Ellen, who married Mr. Henry Smith, of Drax

Abbey, Yorkshire.

Bernard became a physician, and died comparatively young. Albert went to

Canada.

Father Furniss received his early education

first under the care of the Franciscan Fathers at Baddesley, near Birmingham.

He was then sent with one of his brothers to Sedgeley Park School in Staffordshire,

where he was a year and a half, and amongst his fellow-scholars was Canon

Frith. From Sedgeley Park he was removed to Oscott College, where he remained

about two years, and finally in his sixteenth year he went to Ushaw.

One who knew Father Furniss later on in his

religious life, writes as follows: "Though no one can now doubt that he

was called into being by God for the wonderful work which that God, the lover

of little ones, later inspired him to do, yet no one in Father Furniss's

earlier years would ever have dreamed of the future that lay before him, no one

would have thought he was called to anything extraordinary. He was a good and

pious boy, but remarkably timid and shrinking. At school and at

college—although he shewed, I believe, no mean talent—he suffered a great deal

from his companions, who ridiculed and teased the bashful, awkward child. His

sallow complexion caused him to be called 'Black jack,' a nickname which drew

many tears from him, and which in his last troubled days he recalled as an evil

omen, poor man! He was as sensitive a child as he was a timid one. Some took

advantage of his unresisting meekness to add blows to words, and torment him in

every ingenious way known to school-boys. To make matters worse, some of those

placed over him were harder upon him than even his companions. In his later

years he used to relate stories of these early trials, and tell how they had

taught him to pity and feel for children's sorrows, and in this way had been a

help to him in his work for them."

On this period of Father Furniss's life

Monsignor Croskell, the venerable Provost of Salford, thus writes:

"I remember the late Father Furniss

coming to Ushaw College.

He had commenced his ecclesiastical studies at Oscott, and when he came to

Ushaw was placed in the class of Syntax or Poetry. I remember that he used to

gain good places in his class at the quarterly 'readings up,'—not the very

first, but second or third. Hence we may conclude that he was of fair ability,

and a diligent student.

"To illustrate what indeed appeared

through his whole life, that he was naturally of a delicate constitution, I may

mention that owing to his sallow and bilious complexion he got the college name

of 'Black Jack.' Boys are no respecters of persons, but their random shafts

often point to some truth or peculiarity of character.

"To illustrate Father Furniss's love

of study, I may mention a simple incident which occurred when he had advanced

to the class of Theology. At that time there was no gas in the College, and

students had to be supplied with mould candles, calculated to last so many

hours of study, and a trifle over for going to bed after the last prayers. A

student was appointed to go round from time to time with a supply of candles.

It happened that one young school-fellow, Charley Radcliffe, was appointed to

that office at the time. He came down one day with what we considered a smart

saying of Mr. Furniss, from which we may infer that he exceeded the College

hours of daily study in poring over his books. He said to Charley on entering

his room with his supply of candles: 'Charles, yours are like angels' visits,

few and far between.' He had, no doubt, to spend some of his pocket-money in

getting extra candles for extra hours of study.

"From the next anecdote we may perhaps

suppose that John was then somewhat of a judge of fine art, and fairly well up

in history and biography.

"It was probably before he received

Minor Orders that he was balloted to serve in the Militia, and had to go to

Newcastle, either to get exempted, or to pay for a man to serve in his place.

He went in company of a superior. At that very time Madame Tussaud was first

exhibiting her far-famed wax-works, and going from town to town with them. She

was then in Newcastle. Mr. Furniss must of course be allowed to visit the

Exhibition. Whilst there he stood fixed in admiring wonder, looking at some

historic figure. A number of the visitors took him for a part of the show, and

were gathering round him to inspect him thoroughly from head to foot, when he

dispelled the illusion by quietly moving on. One may construe this incident as

a sign of young Furniss's admiration of heroic characters and historic names.

"This my idea of his early taste for

literature, history, and the fine arts may gather a shade of confirmation from

the character of his native Sheffield, which had the fame of being a literary

town, and distinguished by men of letters; and he may in his early years have

caught the spirit of his native town."

However this may be, we may well believe

that Father Furniss cultivated a taste for literature in his College days from

the pure, lucid, and simple style, as well as the happy use of imagery and

graphic illustration, that characterised the little books which later on he

wrote for children. When Father Furniss had been at Ushaw one or two years, his

former school-fellow Canon Frith rejoined him there, and was with him in the

school of Divinity. It is said that he distinguished himself amongst his fellow-students

in philosophy and theology, and uniformly edified them by his piety.

Father Furniss was ordained priest by

Bishop Briggs, Vicar Apostolic of the Northern District, who was at the same

time President of the College, May 24, 1834. In becoming a priest he attained

what from early childhood had been the one object of his ambition.

——✤——

First Years of Priesthood.

Bradford and

Doncaster.—(1834-1840.)

e learn from the Ushaw Chronicles that Father Furniss

resigned his minor professorship of Poetry into the hands of another, June 9,

1834, and on the 18th of the same month left the College for Hesleyside,

"in vineam Domini." If he was destined in the first instance for the

mission of Hesleyside, his stay there was for but a few days; since his name

appears on June 29, in the Register of Baptisms at St. Mary's, Bradford, where

he remained some time over one year. During this period are also in the

Register books, together with that of Father Furniss, the names of the Rev.

George Corless, Charles Pratt, Philip Kearney, John Rigby, and Peter Kaye, who

was in charge of St. Mary's for some years. The date of Father Furniss's last entry

is July 23, 1835. I have been unable to learn anything more of him during his

year at Bradford, except that there are some still living in the parish who

remember him as a priest there.

About the month of September, 1835, Father

Furniss was sent as the first resident priest to Doncaster.

This mission had been commenced in 1833. It seems that some buildings in

Prince's Street, consisting of a stable and coach-house, were then purchased and

converted into a school-room; and here a priest from Sheffield used to say Holy

Mass occasionally. Father Furniss purchased a house in Prince's Street, adjoining

the school-room, which he converted into a chapel, effecting for himself a more

ready access to it by making a door through the side wall of the house. Here Canon

Frith, who gives these details, remembers paying him a visit for a few days.

The chapel bore the title of St. Peter ad Vincula, which the present church still

retains. This was erected twenty-seven years ago in Canon Pearson's time on the

site of the old buildings.

"The bigots of Doncaster," says

Canon Frith, "were not long before they made an attack on Father

Furniss—and in particular a Church of England curate in the town—by publishing

rancorous and calumnious articles and letters against him and the Catholic

faith in the Doncaster Gazette and

other newspapers. But they found that they had caught a Tartar, and that he was

more than their match. They were soon silenced by his able, incisive, and sarcastic

replies. Father Furniss in his early days at Doncaster devoted much time to this

controversial correspondence, and many of his letters were of considerable

length."

From the Rev. Charles Burke, who later on

was for many years the parish-priest at Doncaster, I have gleaned what remains

in this chapter of the life of Father Furniss during the five years that he had

charge of the mission.

He showed great zeal for the House of God, and

the spirit of faith and piety that animated him, by his strict observance of

all the ceremonies and rubrics of the Church, as far as the circumstances of

the mission would allow, and by the care that he took to beautify and adorn his

poor little chapel. The six handsome silver-plated candlesticks, the silver

cruets and stand, and the silver thurible, which are all still in use, were

gifts of Father Furniss. He was assiduous in preaching, in instructing the

people from the pulpit, and in visiting them in their homes. He very soon

prepared a number of the children and adults for the sacrament of Confirmation,

which Bishop Briggs came to administer. As there was not at that time any

railway communication from York, where the Bishop then resided, he had to drive

to Doncaster in a one-horse carriage, attended by his faithful bandy-legged

servant, Matthew, a well-known character at Ushaw and throughout the Northern

District, who acted as his Lordship's groom, valet, and general factotum.

The sick and poor especially ever found in

Father Furniss a devoted friend. For he not only attended diligently to the

spiritual needs of the sick and afflicted, but never failed in his large

charity to minister to their temporal wants also, by sending them wine, more

delicate and nutritious food, and what other remedies they might require. For

the poor he had a very tender care. A certain number of the aged and infirm

were his constant pensioners, and came regularly to his house to receive their

portion of soup and meat, and loaves of bread. Many a casual beggar and tramp

too, who had heard of his benevolent bounty, would come to seek his help, and

never went away unrelieved.

After Father Furniss had lived some time

near the chapel, and his health was beginning to be

impaired through weakness of

the heart and bronchial affection, he removed at the earnest entreaty of his

sister and her husband, Mr. Henry Smith, to Hall Cross Hill.

Here he was visited by his favourite brother Bernard, a physician, then in the

last stages of consumption. He died soon after at Drax Abbey.

Father Furniss was always fond of a good horse, and used frequently to ride.

His brother left him an excellent carriage, of the use of which, in his

delicate state of health, he now availed himself. But not long after his

brother's death he became himself seriously ill; and, being unable to leave his

house and go to the chapel, he converted the drawing-room into an oratory,

where he frequently said Mass. As his health did not rally, he was advised by

his physician, Dr. Scholfield, to give up all thoughts of further clerical

work, and, as a last resource for prolonging his life, to go abroad and try the

effects of a warmer climate.

——✠——

Sojourn of Several Years abroad.—(1840-1847.)

ather Furniss left England for southern Europe in 1840, and

spent some six or seven years travelling about through Italy, the Tyrol, Spain,

and the East. This he did principally in hopes of regaining his health, and

returning to his work as a priest; but also to satisfy his piety, by visiting

the most famous shrines of Our Blessed Lady and the Saints. Father Furniss

throughout his life evinced uniformly a serious purpose of sanctifying his soul

and serving God in the way of perfection; and there is testimony from one who

knew him well at this period that he was then much occupied by these thoughts.

Hence, wherever he went, his chief care and occupation was to foster and

increase this spirit of piety by devoutly frequenting the churches, the holy

sanctuaries and shrines of the Saints, and spending much time in reading their

Lives, in prayer, and meditation.

He was careful to note down whatever

specially interested and impressed him in his travels, and he thus laid up a

large store of anecdote and story with which he would often illustrate his

discourses and instructions later on in his Children's Missions. He was a very

attentive and keen observer of all that he saw, marking the surrounding scenery

and the minute topography of the places he visited, so that the vivid and

accurate impressions, thus formed and retained in his memory, gave him that

marvellous power which he had in after years of fascinating his hearers by his

graphic descriptions. His interest in ecclesiology and archeology was great,

and led him to collect here and there in his travels a large number of holy

relics, pictures, and other objects of sacred and antiquarian art, which he

brought home with him; and one or another of them he would sometimes exhibit to

the children.

During his sojourn abroad he kept up

diligently the study of theology, and especially of Holy Scripture. This is

shewn by the copious notes contained in the manuscript books which he wrote at

this period, and which are still preserved. He generally spent the winter in

Rome, and went elsewhere during the warmer season. At Rome he used to attend

the lectures on moral theology held in the Roman College. He had ever a

particular devotion to St. Alphonsus Liguori and his writings. His attraction

to the holy Doctor's Moral Theology was such that he always had with him

Neyraguet's Compendium, and would take it out to read from time to time on his

journey. In 1842 he made at Rome the acquaintance of Monsignor Weld, which soon

ripened into intimacy, and from October, 1843, to June, 1844, he used to dine

every day with Monsignor Weld in his apartments. We may learn something of

Father Furniss's English contemporaries at that time in Rome from the following

extract from Lucas's True Tablet,

August, 1842.

"The Right Rev. Dr. Wiseman arrived at

the English College on the 14th inst. . . . A few evenings ago I was

at a defension, in its fine Hall, of a logical and metaphysical thesis by a

younger son of Lord Clifford, William to wit,

Cardinal Acton presiding, and Drs. Wiseman, Baggs and Grant objecting. The

young gentleman acquitted himself of his task in a distinguished manner, and

much to the admiration of his learned and venerable audience."

Father Furniss during all this time was in

very precarious and delicate health; and no one thought that he would resume

again any active work. This appears from another cutting of the same issue of

the True Tablet: "The Rev. John

Furniss is again better, but fears are entertained that he will not be able

again to bear the climate of England."

Amongst the remedies prescribed for him was

goat's milk, about which he used to tell an amusing incident that occurred in

his Spanish pilgrimage.

As it was extremely difficult to procure fresh goat's milk every day, on one

occasion at least he took with him a goat in the diligence. His fellow travellers

were highly amused, and I believe sometimes milked the poor animal on their own

account. From this incident, some have drawn a long bow and maintained that

Father Furniss took a goat about with him wherever he went during all the years

he was abroad.

The following letter from the Rev. Father

Douglas, describing Father Furniss's tour in Palestine, will be read with

interest:

"Rome, January 16, 1889.—In the

beginning of April, 1845, Father Furniss started from Rome in company with the

late Mr. Carrington Smythe, son of Sir Edward Smythe of Acton Burnell, Mr. Hamilton,

and your humble servant, for Palestine. We came by steamer through the Straits

of Messina to Malta, and from thence to Constantinople, to Smyrna, Rhodes,

Larnaca in Cyprus, and so to Beyrût in Syria, where we arrived on the 2nd of

May; a month having been spent at the above named places. Having procured the

necessary things for travelling in those days, and servants, we rode on

horseback to Djebail, and turning short of Tripoli, entered the Wady Kadiska or

Holy Valley, in which at Dimam we visited the Patriarch of the Maronites. The

third night after our departure from Beyrût, we slept under the cedars of

Lebanon, and then crossed the chain to Baalbek or Heliopolis, where we passed

Whitsunday and assisted at the Mass of the Greek Melchite Bishop, as Father

Furniss—not having a portable altar or vestments—could not say Mass. Two days'

more riding, and passing the nights in tents, brought us to Damascus. The war

had broken out between the Druses and the Maronites, so in attempting to pass

from Damascus to Panias (Cæsarea Philippi) we fell into the hands of the

Druses, and had to retreat to Damascus, whence after some days the Pasha gave

us a Turkish guard to convey us over the Lebanon to the camp which the Pasha of

Beyrût had pitched on the western slope of the chain. From Beyrût we took a

boat to Caifa under Mount Carmel, and from thence on horseback to Carmel,

Nazareth, Mount Thabor, Tiberias, the Sea of Galilee, Cana, and again to

Nazareth and Acre. Thence we went by boat to Jaffa, and again on horseback to

Ramleh and Jerusalem.

"Arriving in the Holy City on the 1st

of June, we stayed there until the 17th, visiting Bethlehem, St. John in

Montana, and all the other sanctuaries. Father Furniss celebrated Mass in the

Holy Sepulchre, and gave us all Communion, after having passed the night in the

adjoining building occupied by the Franciscan Friars. Father Furniss went to

the Jordan and to St. Saba, which I did not, being tired out. From Jerusalem we

went to Gaza, and then had an eight days' journey on camels across the desert

to Cairo, where we arrived on the feast of SS. Peter and Paul. Some days in

Cairo and a visit to the Pyramids brought us to the time of the Indian mail

from Suez (there was no canal then), and so we got to Alexandria, and thence to

Naples, where Father Furniss remained. This was in the latter half of July,

1845."

During their sojourn in Egypt they talked

over the idea—Father Furniss, it is said, seriously—of becoming hermits in

Egypt, in imitation of the Fathers of the Desert.

His travels, especially those in Palestine,

were of great use to him in his Children's Missions in after years. His graphic

descriptions of the spots connected with his Gospel and Scripture stories,

which he had seen with his own eyes, led some of the very little ones to

believe that he was as old as the Wandering Jew or older, and had been a

witness of the stories as well as of the spots. His venerable appearance

confirmed this conclusion in their innocent minds.

——✤——

Return to England. Visitation

Convent. Work

in London. Vocation to the Redemptorists.

—(1847-1850.)

ather Furniss returned to England from his long sojourn

abroad in the year 1846 or 1847; and the next that we hear of him is from the

Convent of the Visitation at Westbury-on-Trym, near Bristol, where he was

chaplain to the nuns in 1847, and remained so about a year and a half. In

answer to my enquiries, through the kindness of the Rev. Mother Superior, I

received the following reminiscences of him at this time.

"There are three Sisters in the

Community still living who knew Father Furniss, and I have been trying to

ascertain all I could from them; the information is, however, but small.

"They tell us that Father Furniss had

an extraordinary devotion to Our Blessed Lady. He had a picture of Our Lady,

which he said was miraculous, and before which he had evidently obtained some

special favour. This picture he used to pass through our grating on Sundays,

and the Sisters used to carry it in procession, and on the Sunday evening it

was returned to the Father. On leaving us to join your Order, he gave us the

picture on condition that we should always burn a lamp before it, which has

always been done. It is quite of the style of the old miraculous pictures—Our

Lady and the Divine Child in her arms, in dark colouring. Every one here has a

great devotion to it. It forms the altar-piece of Our Lady's Chapel within the

Monastery.

"Father Furniss undertook to explain

the whole of the psalms of our Office (Our Lady's) and of the Office of the

Dead, assembling the Community twice a week for the purpose. He had great zeal

for the conversion of sinners, and used to make a list of names, which he

recommended on Saturdays. He was full of charity for his neighbour, and was

ever ready to help the poor in their needs. Once a young man presented himself

under the plea of wanting to be instructed in the true Faith, but really to get

some clothing. The Father was so moved by his poverty that he went to his

wardrobe and gave him his own great-coat; he never saw the man again. I should

have said that when questioned as to the grace he had received before the

picture of Our Lady, he used to cast his eyes down and keep silence, and would

not reveal what had passed."

From the Convent of the Visitation Father

Furniss went to London in 1848 or 1849, where he was for some short time with the

Rev. Frederick Oakeley, assisting him in the work of his extensive and populous

parish of Islington. Here he occupied himself in gathering in from the crowded

lanes and by-ways of the district the poor Catholic children, who were very

numerous in consequence of the recent large immigration from Ireland, and

necessarily in a state of great neglect, as the schools for them had not then

been built, and priests to care for them were at that time very few. Father

Furniss spent himself in instructing large numbers of these little waifs and

strays, as well as bigger boys and girls, whom he gathered together out of the

courts and alleys, and prepared many of them for Confirmation and Holy

Communion. It was now for the first time that he began to be conscious of his

predilection for children, and also of the great power he had over them.

Here in 1850 he met again his old friend,

Monsignor Weld, and also Father Douglas, who had meanwhile been ordained

priest, June 25, 1848, and had made his profession as a Redemptorist, December

8, 1849, and was then attached to the Monastery of St. Mary's, Clapham.

"Up to this time," writes Father

Douglas, "he had had no particular liking for children, but then this love

began to spring up in him, and he began to exert himself with the greatest zeal

in the courts of London amongst the little ones. It was now at length, too,

that he turned his attention to the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer,

having always had a very special drawing to St. Alphonsus."

The late Father James Bradshaw, C.SS.R.,

writes of him at this period as follows:

"I met Father Furniss for the first

time after leaving College at a soirée held at that time the Tuesday in each

week at the house of Cardinal, then Bishop, Wiseman in Golden Square. It was in

the spring of 1850. I had charge of a small parish at Croydon. I invited him to

come and preach for me on the following Sunday, which he did. Before parting

that evening, we agreed to go and make our annual retreat at the novitiate of

the Redemptorists at St. Trond. Neither of us owned to a sneaking intention of joining that Order. At the appointed time I

wrote to his Reverence, and fixed the day of our visit to St. Trond, but his

reply was, 'Not this year, I have another engagement;'—he was starting a new

mission at Peckham. I went off alone to Belgium, and finished by postulating,

and being admitted into the Congregation of St. Alphonsus Liguori. On returning

to the Redemptorist house at Clapham, I found that Father Furniss had just gone

through the same process there, and had resolved to become a Redemptorist. We

arranged the time for our departure to the novitiate in a couple of

months."

The Redemptorists had but recently come to

London, and through Cardinal Wiseman had been established at Clapham. Father de

Buggenoms whom Father Furniss had met in London, was chiefly instrumental in

drawing him to the Congregation, of which Father Douglas and another priest

whom he had known intimately in Rome were already professed members. He was

moreover especially attracted to the poor, and he saw that the work of the

Redemptorists was principally for the poor and the most abandoned souls. The

vast multitude of poor Irish driven into England by the famine, and in extreme

need of spiritual succour, excited his compassion, and he felt that in the

Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer he would be able most effectually to

labour for them, and above all help the poor children, who had now become so

dear to his heart. Such appear to be the chief motives by which God drew him to

his vocation as a Redemptorist.

——✤——

Novitiate at St. Trond.—(1850-1851.)

ll who knew Father Furniss were astonished when they heard of

his resolution to enter the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, and many laughed

at him for entertaining the idea, and at the Redemptorist superiors for receiving

one so weak, broken down, and prematurely aged as he appeared—though he was

only in his forty-first year. He was received by Father de Held, then stationed

at Clapham as Visitor of the English Houses, and with the sanction of Father

Deschamps,

the Provincial of Belgium, to which province Holland, America, and England then

belonged. Father Furniss was sent in the summer of 1850 together with Father

Bradshaw to the novitiate at St. Trond, where Father Paul Reyners was

novice-master at that period. They were expected to arrive in good time to make

the fifteen days' retreat before the Nativity of Our Blessed Lady, on which

feast they were to receive the holy habit. The days passed on, and there was no

sign of the expected postulants. Father Paul wrote to Father de Held, who could

only reply that they had left Clapham for St. Trond days before, and that he

had thought they had long since arrived. The fact was that Father Furniss had

not lost his old love of making pious pilgrimages, and, judging probably that

this was his last chance of making one, he proposed to Father Bradshaw, on the

way over from Dover to Ostend, a pilgrimage to Our Lady of the Hermits at

Einsiedeln in Switzerland. To this proposal Father Bradshaw readily agreed,

thinking that they would reach St. Trond in time for the commencement of the

retreat. But somehow their pilgrimage took nearly three weeks instead of one

week, as Father Furniss had supposed. At length, on the evening of September 7,

the wanderers arrived at St. Trond. Father Paul, in very bad humour, inquired

the meaning of the long, and so far unexplained, delay. Father Furniss with

perfect simplicity said that it had struck them on their way to go as pilgrims

to the shrine of Our Lady of Einsiedeln, to ask her blessing on their vocation

and novitiate, and that they had hastened to be in time to get the habit on the

morrow. Father Paul answered indignantly, "There was now no question of that,—they had not made the retreat

which the Holy Rule required," etc., etc. "Was not a pilgrimage to

Our Blessed Lady as good as a retreat?" put in Father Furniss. "You may think so," replied

the incensed novice-master, "I

do not."

They consequently only received the habit on October 15, the feast of St.

Teresa, when Fathers Plunkett and Bridgett received it also.

Amongst the thirty and more novices then at

St. Trond, Father Furniss, from his being much older than the rest, was rather

prominent, and was constantly brought forward by the novice-master for remarks

or criticism. As all who knew Father Paul are aware, though kindest of the

kind, he tried his novices in every possible way, and was specially on the

look-out to try priest-novices, believing they needed it more than others, if

they were to become true child-like Redemptorists. Father Furniss's antecedents

secured him an additional share of these attentions of his novice-master. The

humiliations he received were not perhaps very severe; but whatever they were,

he bore them all bravely and good-humouredly. He was frequently accused in

Chapter by the youngsters for want of personal cleanliness and neatness. Indeed

he was habitually—in later life too—slovenly, very negligent about his external

appearance, untidy and disorderly. He felt much these accusations, but bore

them well. He gave great edification to all who were with him in the novitiate

by the great fervour with which he went through the various spiritual exercises

of the day, by his observance of the Rule, and general spirit of prayer and

piety. Thus he was habitually to be seen in the chapel every morning a quarter

of an hour before the bell was rung for the early meditation at five o'clock.

He excelled especially in devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and there may still

be seen before the statue of Our Lady in the corridor the lamp which he gave to

be placed there, and which he took care, as long as he was at St. Trond, should

be always kept burning at his own expense.

Though no longer young, and continually

suffering from feeble health in consequence of heart and bronchial affections

of many years' standing, he went through his novitiate with hardly any

dispensations from the ordinary rule. He was distinguished for his uniform

gaiety and cheerfulness, being the life and soul of the recreation, fond of

talking and relating stories; and, as his French was very English, he was a great source of fun to his fellow-novices,

amongst whom he was a great favourite, especially with the younger ones. They used

to call him "the old man," and delighted in teasing him, whilst he in

turn showed himself not unwilling to be teased. His playful ways and innocent

tricks won their hearts; he freely indulged in badinage with them, and was ever fond of a pleasant joke. This

characteristic of Father Furniss was very useful to him later on with his dear

little ones. Moreover it endeared him to his confrères, wherever he went, and

clung to him to the very end—amidst his wonderful successes, in the trials and

contradictions that surrounded him for years, and even in the terrible sorrow

of his last years, which formed the old man's crucifixion. Whilst still on this

subject, I will quote the words of a Father who was one of his co-novices, from

a letter dated April 15, 1895:

"What struck me most in Father Furniss besides his wonderful zeal

for the work of the children, was his invariable good humour and gaiety of

manner, in spite of his serious and almost continuous infirmities. He was full

of fun; and his fun was not altogether free from a certain amount of innocent

malice. His piety was evident, and it was this which gave him such power over

the children. They always considered him a real saint."

Father Furniss's seven years of pilgrimage

proved always an interesting, amusing and edifying subject for conversation during

the novitiate. He seemed to have visited every noteworthy place that the novices

had read of in the Lives of the great Catholic Saints, especially of Italy and

Spain: with the sanctuaries of France and Germany he seemed to be little

acquainted.

He did not, when a novice, forget the poor

Catholic children for whom he had laboured so zealously in London, but bore

them still in his heart. His vocation, indeed, to be the Apostle of Children

already showed itself in the novitiate, at least to this extent, that he took

the most lively interest in all that concerned them, often saying that he loved

to labour amongst them, and hoped one day in the Congregation to be allowed to

consecrate his life to work for them. He was careful to gather and note down

from his spiritual readings in the Lives of the Saints all the anecdotes he met

with about children, and whatever else particularly struck him as bearing on

them and work for their souls.

No doubt his recent labours for them at

Islington, his experience of their destitution and needs, led him to these

thoughts, especially now that he had joined a Congregation which was devoted to

giving missions. For this was just the time when missions were beginning generally

to be given in England, and much enthusiasm was enkindling about them. The

Order of Charity and the Passionists were most of all distinguished in this

work, not however for anything they had done particularly for children. Still

some work of this sort had been done for them by zealous secular priests,

Fathers Kyne, Hodson and others, whom Father Furniss had known in London and

had been emulating at Islington. In after years, looking back on these his

first missionary efforts amongst children, he would speak of them as utter

failures. The manner of preaching and instructing which he then adopted, was,

he said, radically wrong.

The weakly state of Father Furniss's

health, which had increased at St. Trond,—his more advanced age—the very

edifying way in which he had gone through his probation, and the evident signs

he had given of a true vocation, led his superiors to shorten considerably the

time of his novitiate, and he was admitted to his religious profession on the

feast of the Visitation, July 2, 1851. Thus did Our Lady of Einsiedeln make up

to him by months the weeks of delay in his receiving the habit which his

pilgrimage to her shrine had cost him.

After his profession he went to the Redemptorist

house at Liége, where he remained for more than two months. Here his health

improved, and he occupied his time with theological studies in preparation for

his approaching mission work.

In the month of September he left Liége to return to England. On the way he

paid a short visit to St. Trond. There were then in the novitiate, besides the

English novices before mentioned, Fathers Stevens, Coffin (afterwards Bishop of

Southwark), Vaughan, and Gibson.

Father Lans, who had been for six years Superior of the house at Hanley Castle

in Worcestershire, was then at St. Trond. He had been there for the last five months

preparing himself for the office of novice-master of the then contemplated

English novitiate at the new foundation of Bishop-Eton. Father Furniss left St.

Trond with Father Lans for England, and arrived at Clapham September 24, 1851.

They broke their journey for a few hours at

Bruges in order to pay a visit to the Convent of the Redemptoristines in that

city. Sister Marie Jean de la Croix, who a few years later was sent to Dublin

to found there a Convent of the Order, and was for many years the Mother

Superior at Drumcondra, gives the following particulars of this visit.

"Monastery of St. Alphonsus, Dublin,

Dec. 13, 1888.—I saw the Rev. Father Furniss in Bruges, after his holy

profession, when returning to England. All the Sisters went to the parlour, as

his Reverence had never seen a community of Redemptoristines. We were much

edified by his love for his vocation and for his holy Father and Founder St.

Alphonsus. He showed us all the beautiful relics that he had brought from Rome,

the Holy Land, and other sacred places which he had visited in his travels. On

the Rev. Mother asking for some of the relics, he said, 'I shall give some later

on to the Redemptoristines who will cross the sea and come to England,' adding

in fun, 'Who is ready to come?' I stepped forward without ever thinking such a

thing would be realised, and said, 'I am ready, if obedience sends me.' The

Rev. Mother then said, 'Reverend Father, you should put the Sister's name down

in your diary.' When Father Furniss was in his last illness, I sent him word

that he should remember his promise about the relics. Whereupon he sent me

several cases of relics, which are now venerated in the church of our

monastery."

——✤——

First Missions in England and

Ireland.—

(1851-1855.)

fter remaining three months at Clapham, Father Furniss was

sent to take part in a large mission at St. Nicholas, Copperas Hill, Liverpool.

This was the first of a series of 115 missions and retreats given by him during

the ten succeeding years.

In his third mission, which was at Woolton, near Liverpool, his peculiar talent

for directing children first displayed itself. With Father Furniss were two

other Fathers under Father Lans as Superior. The Father who had charge of the

children, however otherwise zealous and devoted, could not succeed in keeping

them in order. Father Furniss, observing this, begged Father Lans to allow him

to try whether he could not succeed better. His management proved to be so

admirable, that from that time, in all the missions in which he had a share,

the care of the children was assigned to him. It was not, however, until after

some few years that he gave separate missions to the children. He began by

going with other Fathers on the general missions; and in these the children

were his special charge. He took care that every morning they came to what then

first began to be called the Children's

Mass, when from the mission platform he directed their devotions, and

explained to them the nature and ceremonies of the Holy Sacrifice—and after it

was over gave them an instruction. He heard their confessions, prepared them

for Communion and Confirmation, and directed their General Communions. As the

church was occupied at night by adults, he assembled the children every evening

for their mission service in the school-room, which however was generally much

too small for their numbers. Father Furniss soon discovered that this system of

giving missions to children was very imperfect and unsatisfactory. The results

were not at all such as he desired. The children were quite at a disadvantage,

and their needs were but inadequately supplied, when their mission was given at

the same time as that to the adults, by which it would necessarily be

overshadowed. He was fully persuaded that something much better could be

planned. But it was no easy matter for him to obtain permission to give

separate missions for the children. This was a novelty, which would be at once

in some quarters its condemnation. Besides, the demand for missions was so

great, and the missioners were then so few, that he could not be spared for a

separate work. Hence he met with much opposition, both from some of his confrères,

and also from superiors, though on the whole these latter supported his views,

especially Father Lans, the then Vice-Provincial, who, seeing the great good he

could do, was his best friend in the matter. Another difficulty was that these

Children's Missions did not pay the expenses necessarily incidental to them.

Moreover, it was held by many that, owing to the vast number of children

flocking together, such missions would be sure to prove dangerous and

disorderly. Father Furniss, however, in course of time gained the victory over

every opposition, and was at length allowed to have separate Children's

Missions: and this practice was confirmed by a decree from Rome of the Father

General, in the year 1855. From that date all the missions which Father Furniss

gave were of this description.

During the previous years, however, his

work was almost exclusively confined to the children, and on a few occasions he

had given separate missions to them. Thus in the year 1853 at the desire of the

administrator of St. Michael's, Limerick, he gave a Children's Mission in that

parish, and at its close founded there the Confraternity of the Holy Family for

Girls.

The following account of this mission was

furnished by one who herself took part in it, and has been for many years a

Redemptoristine Nun at Drumcondra.

"In 1853 the Rev. Father Furniss

arrived with several other Fathers at their temporary residence in Bank Place,

Limerick, where they attracted crowds to their little chapel, which consisted

of two parlours with the partition door removed at the time of any public

service. From the commencement Father Furniss's love and zeal for children were

most remarkable. In the year 1853 he gave a mission to them in St. Michael's

Church, at the close of which there was a very large General Communion, of most

for the first time, and instituted the Confraternity of the Holy Family for Girls.

When this was fully organised in the summer of the same year, there was another

General Communion of all the members at St. Michael's; and afterwards they

walked together, followed by the Rev. Father, to the Northumberland Buildings,

where a breakfast was provided for them. In his familiar address on this

occasion, he told the children to beware of admiring their dresses, lest the

devil might be found sitting on the tail.

"It would be impossible to exaggerate

the amount of good effected by this Confraternity, which in a short time

numbered more than 400 girls. As long as Father Furniss remained in Limerick,

he was its Director. On Sunday afternoon, the Rosary having been recited, he

gave an instruction in that sweet simple way of his, which impressed all his

young hearers so profoundly. He also gave Benediction of the most Blessed

Sacrament, during which the girls, taught by his Reverence, sang with great

fervour the Litany of Loreto, etc., followed by a hymn in honour of Our Lady.

Suffering, as he did at one time, from a severe cough and delicate chest, he

was recommended to abstain from his usual custom of singing the hymns and

litanies with the children. He allowed them therefore to commence; but no

sooner had he heard the children's voices than he forgot everything else and

joined in with them, being unable to resist the holy joy he felt in the

devotions of the little ones. He had several pictures which he used to shew

them; amongst others a copy of the Madonna painted by St. Luke. This picture excited

great admiration, not only among the children, but also amongst all those who had

seen it, not so much for the picture itself, but because Father Furniss had a

picture of the Blessed Virgin painted by St. Luke. He had also a little bottle

containing water from the Dead Sea, and this he used sometimes to bring forth

in his instructions on the punishments which are inflicted on sin.

"To this Confraternity was attached a

library consisting of Lives of the Saints and other pious books, which were distributed

gratis every Monday on condition of

their being returned the following week. They were often brought back by the

fathers and grandfathers of the girls, of whom many were at work in the public

factories and unable to come themselves; and it was touching to hear them say

what good these books had done for them and their whole families. The little

ones, accustomed to address secular priests only, would answer the Father:

'Yes, sir; No, sir.' Father Furniss did not like this, and would say: 'Call me Father, not sir.' The ladies who

directed the Confraternity were ever in the greatest admiration at the untiring

zeal, forgetfulness of self, and devotedness, with which Father Furniss gave

himself to the Association; and many of the children who in the beginning were

wild and unmanageable, under the Reverend Father's wonderful influence and

winning manner, became quite docile and very pious. On returning from the

meetings, some of the children, full of faith, would often join hands in a

circle in front of the houses of some very bigoted Protestants, and, bowing

towards their windows, would sing with the greatest animation, 'Daily, daily

sing to Mary,' thus proving what zeal for our sweet Mother's honour had been

implanted in their brave hearts by this true son of St. Alphonsus. After Father

Furniss's departure from Limerick, the Rev. James Synan, administrator of St.

Michael's, kindly gave his full support to the Confraternity, spent several

hours of each Sunday afternoon with the children—as did their deeply regretted

Director, who had won the hearts of all,—and gave every encouragement to a work

which he considered one of the greatest blessings that the parish enjoyed.

However, on Father Synan's promotion to the parish of Shanagolden in 1859, his

successor, finding the occupation of the church for so much time on Sundays

very inconvenient, did not patronise the Confraternity, and the good ladies

were most reluctantly obliged to abandon the work so dear to them and to its

holy founder. Many and many were the deep regrets expressed by the parents of

the girls, when they heard of this determination; they said God alone knew from

what dangers the Confraternity had preserved their girls, and what advantages

they had gained by regular attendance at its blessed meetings."

The following reminiscence of the mission

at St. Michan's, Dublin, 1855, is given by a Redemptoristine Nun.

"A carpenter was fixing some presses

in our Sacristy a few years ago, and the Sister who overlooked the work asked

him if he was attentive to his religious duties. He replied, 'I have not time

to do much, but I have never forgotten one little practice taught us long ago

by one of the holy Fathers who was a Saint; Father Furniss was his name. During

the mission of Anne's Street, he told us we need not go on our knees to pray,

but we should from time to time raise our hearts to God during our work, and say,

My Jesus, I do this for the love of Thee. I can never forget the impression the

sermons of that holy Father made upon me, and very often during my work I say

the little prayer he told us.' This simple avowal explained something which had

often surprised us. We noticed that this carpenter often touched his cap

without apparent reason, but we were far from suspecting that he was breathing

the little aspiration he had learned so many years ago from the zealous

Redemptorist, who, he said, was a 'grand preacher and must be a great Saint in

heaven.'"

A Father who has grown grey in our

Congregation gives the following particulars of one of Father Furniss's

earliest Children's Missions in England.

"Let me tell you of my first meeting

with Father Furniss, and the impression it made upon me. The remembrance is yet

fresh, though over forty years have passed since then. It was in 1854. I was

close upon eighteen. A Children's Mission was going on at St. Oswald's, Old

Swan, near Liverpool. I was staying on a visit with my brother, and was constantly

at Bishop-Eton which was only two miles off—already for several years a child

of the Congregation in heart and desire. When I heard from the Bishop-Eton

Fathers what was going on, I made my way to St. Oswald's. It happened to be the

night of the children's consecration to Our Blessed Lady. I was not allowed to mingle

with them, but by arriving very early managed to get amongst the adults in a

corner where I could see and hear everything. I was indeed wonderfully impressed.

A beautiful altar of Our Blessed Lady, one mass of flowers and lights; a

venerable white-haired priest on the platform talking in simple, child-like,

but tenderest accents to the little ones; the church packed to overflowing with

eager delighted children, whose eyes never strayed from preacher or altar,

whose ears drank in every word, whose faces glowed while they listened

spell-bound, sometimes smiling, sometimes shedding sweet tears, as the

story-teller played on the chords of their little hearts. I think Father

Furniss might have gone on for ever without tiring them. The adults, amongst

whom I was, seemed no less impressed than the children, and smiled and wept

with them. The climax was the Consecration, when the children fell on their

knees with the old man, sobbing as he spoke for them, and then at his

invitation raising their own little voices so sweetly and so lovingly, I had to

cry myself. It was a never-to-be-forgotten scene.

"Scarcely less beautiful was the scene

afterwards, outside, with the sweet chatter of the little ones returning home

happy and jubilant. They belonged to the Blessed Virgin now! She was their

Mother, just as she was to Jesus! She would always take care of them! They did

not need any other mother now! etc., etc.

"Amongst the children were two of my

own cousins, girls in their teens, brought up, alas! in South America, without

piety and with scarce any sense of religion. They were amongst the most

enthusiastic and demonstrative—utterly transformed by the Children's Mission

and that night's scene.

"One only thing pained me, and that

deeply. I heard on the following day the remarks of many of the parents of the

so-called better class, old-fashioned Catholics. They had not been at their

children's consecration to the Blessed Mother, and instead of delighting in the

innocent beautiful enthusiasm of their little ones, they checked it, and threw

cold water on it. The children, they said, should remember the fourth

Commandment; the Father should have taught them to love their own mothers; he

had kept them out too late, had over-excited them, his stories were beyond

belief and foolish, and so on."

——✤——

State of Catholic Children in

England when Father

Furniss entered on his Missions.

ather Furniss did not give full maturity to his method of

dealing with children all at once. This took time for development. During the

first three years and more of his missionary career the chief part of his time

was spent in Ireland, where he took part in upwards of twenty large General

Missions, in which he had the exclusive charge of the children. From time to

time he returned to England, where he joined in the same way in eight General

Missions, and one in the Isle of Man; besides giving three separate Children's Missions.

Until the time came in 1855, when separate

missions to children were formally approved of by his superiors, he was cramped

in his work by many difficulties, and had not free scope for his energy and

zeal. Meanwhile, however, he was, so to say, feeling his way, and continually

gaining a wider and more intimate experience of Catholic children both in

England and Ireland. He learned to know and appreciate better their condition

and surroundings, their most pressing spiritual needs, their peculiar dangers

and disadvantages, and at the same time in what ways he might be best able to

apply remedy and relief.

From May, 1855, to the end of his apostolic

career, Father Furniss's labours were confined exclusively to separate

Children's Missions. Of these, during the six years that remained,

seventy-three were given in England, and eleven only in Ireland. Since, then,

his work lay henceforth almost entirely in England, it will be well to say

something of the condition of English Catholic children at this time.

Father Furniss began his work for children

but a few years after the great tide of immigration had set in to England of

Irish Catholics, forced to leave their native land through the famine and the

general distress which followed it. A vast multitude of the faithful, very poor

and helpless, was thus thrown on the straitened resources of the Catholic

Church in England and Scotland, where the priests were then in scant number,

and the chapels—for they had hardly yet attained to the dignity of being called

churches—small, few, and far between. The pastors laboured hard to provide for

the spiritual necessities of their new charge; but it was quite impossible that

the thousands of Catholic families with which the courts and lanes of the

populous cities and towns now teemed, should be properly cared for. The sick

calls of themselves were enough, together with their other ordinary necessary

duties, to occupy the time and attention of the priests. Hence it is no wonder

that numbers of poor Catholics—now so changed in all their surroundings,

removed from their rural cabins, their country chapel, their parish-priest, who

knew them all so well, to the courts and lanes of the crowded city, unbefriended,

destitute, set down in the midst of so many evil influences and examples without

adequate spiritual provision—it is no wonder, I say, that they should sink into

neglect of religion, of Mass and the sacraments. Meantime had accumulated a

vast multitude of children and young people, who had grown up without any of

the early associations which belong to a Catholic country, without education,

with hardly any religious instruction, who had never been prepared for the

sacraments, and perhaps had never once been taken to Mass. Many of these had

been employed from quite a tender age in workshops, factories, and employments

of various kinds from morning to night; many little girls went very early to

service, or minded babies while their mothers were out at work; whilst a large

number of poor children were waifs and strays about the streets, seeking to

pick up a precarious living by going on errands, and to get here and there a penny

as best they could.

What Catholic schools there were in those

days were very inadequate, and the attendance of the children who went to them

was for the most part very irregular. Parents who had been prevailed on to send

them after much insistence of the priest, would after a short time take them

away to suit their own convenience, or through sheer poverty be unable to

clothe them for going to school, or would keep them at home several days in the

week on frivolous pretexts. We must remember that there was in those days no

compulsory education, and that the present laws with regard to the age of children

going to work were not then in operation. No doubt there were some good

Catholic parents amongst the poor who were careful that their children should

go to school, attend Mass and Catechism on Sundays, and who managed to clothe

them decently; but these children were comparatively few and might be counted

by the score, whilst the others were in hundreds and thousands—and it was only

these few who came under the influence of the priests and, as a rule, were

prepared for their confession and First Communion.

What was to be done to meet all these

necessities and difficulties? The ordinary parochial organization was quite

unable to cope with them. It was clear that some extraordinary agency must be

called in; and this was that of missions. Missions and retreats are always

necessary from time to time to stir up the spiritual life and devotion of the

faithful. But missions were at that time more than ever necessary as a means of

gathering together the multitudes of Catholics, very many of them quite unknown

to the priests and almost entirely lost to the Faith, that were scattered in

the wide parochial districts which had been newly formed from the great centres

of population. And not only were missions necessary to rally the Catholics

together, but also to enkindle once more their faith and religious spirit by

sermons and instructions, to give them all together a special opportunity of

approaching the sacraments of Penance and the holy Eucharist, which they had

for the most part so long neglected, and thus to bring them under the knowledge

and influence of their pastors, and within reach of the means of grace afforded

to them in the Catholic Church. These general missions were found to be an

efficacious remedy in the case of large numbers of adults who, as a rule, had

been to the sacraments in their early life, before they left their native land.

But what was to be done with the host of children and young people who had

grown up without religious instruction, who did not go to Mass, Catechism or

Sunday School, and had never been to confession or made their First Communion?

The General Missions for adults would not meet their case.

It is, indeed, provided by the Rule of the

Redemptorists that there should be in every mission a Father who has special

care of the children, who instructs and prepares them for their confession and

Communion. But this provision contemplates Catholic children in their normal

state, that is to say, those rather who have been already under some religious

instruction, and more or less going to the sacraments before the mission, or

who, at any rate, were being prepared to receive them. Besides, the Fathers are

so much occupied with the adults in ordinary missions, that they have no time

for duly preparing large numbers of uninstructed children for the first

reception of the sacraments.

Father Furniss was moved with great

compassion at the sight of so many children ready to perish unless timely

succour were brought them; and he was convinced that there was no other way

open to meet the grave necessities of the case, than by setting on foot special

and separate Missions for Children of such a nature that all who attended—even

the most ignorant and abandoned—might be prepared for the immediate reception

of the sacraments. He argued — if they did not make their First Communion at

the time of the mission, when were they to do so? When would they ever have a

better opportunity? When again would they be so well disposed? When more under

the influence of grace? When better instructed as to the nature of the

sacraments, the dispositions necessary to receive them, the truths of faith in

general, and their Christian duties? All that he would require of them, was due

dispositions, and sufficient, though it might be very imperfect, knowledge. And

this he saw the way by God's help to secure to them. And then, even though the

immediate effects of the mission might soon pass away, and they might relapse

again into neglect of their religious duties, and their former sins, still he

considered that their having once received the sacraments well, was a great

boon, not only because of the grace they then received and their conversion to

God, however evanescent it might prove to be, but also on account of the

knowledge which they thus gained, and the impression which all they had gone

through would make on their memory in their after life; since this experience

would serve to shew them better the way to return to God again, should they at

any time have the will to do so, after a life of sin.

Whereas a Catholic who has never made his

First Communion is always at a great disadvantage, and handicapped, so to

speak, even as regards going to confession, so long as he is a young man living

a careless life away from the means of grace, he will hardly have the desire of

going to the sacraments, nor the courage to overcome the shame of being obliged

to tell the confessor that he has never made his First Communion. If however

later on he gets more serious thoughts, and summons up courage to go to confession,

he would go at a time when he knows that the priest is sitting to hear

confessions—say on a Saturday night—and when he is generally occupied with a

crowd of ordinary penitents. Suppose that the man has entered the confessional,

the priest would ask him when was his last confession, and did he then receive

Holy Communion, and on the man's replying that he had never yet been to

Communion, the priest, seeing that the penitent was very ignorant of his

religion, needed much instruction before he could be allowed to receive

Communion, and that his confession would occupy considerable time, would

probably, after saying some kind words of encouragement, bid him come to him

again some evening during the week, when he could take the man's case

thoroughly in hand. Now the chances are that the poor man would feel quite

disappointed at being thus put off, and shrink from the effort of going to the

priest again. For many ignorant people cannot understand the priest's motives

for putting off at least their confession, and this it is which presses most

and immediately on them, so that they have no heart or courage until this is

over. Or something might hinder him from going to the priest at the time

appointed; or the priest might himself be accidentally called away, and his

servant, not knowing the man or his business, might say something which would

seem to him a chilling rebuff. Hence the great effort of this poor man will

probably prove fruitless, and it is likely that he will not repeat it, but go

on all his life without the sacraments; whereas, had the man ever made his

Communion, however long ago, the confessor would feel bound to hear his

confession at once, even though he should have to bid the man come to him again

before going to Communion. In this case the penitent, relieved of the heavy

burden that pressed on him, would be of good heart to return to the priest.

The difficulties in the way of an adult who

has never made his First Communion are indeed so great that, with rare

exceptions, nothing short of the grace of a mission will induce him to go to

confession. But in a mission he sees many like himself, absentees from Mass and

sacraments, going to the missionary Fathers. He has listened to the

instructions and sermons, which have enlightened him and moved his heart.

Fortunate is he if he gets this grace and corresponds with it—but he may never

have the opportunity of attending a mission.

Father Furniss knew all this well, and was

therefore very anxious that as many as was possible of the children who attended

his missions, should then and there receive Holy Communion. But if there were

any about whom he was more solicitous than others, it was the most ignorant,

the most neglected and abandoned. He was anxious also about the younger

children who were at school, for attendance at school was very precarious,

especially that of the poorer children; and for many their school-days passed

away without their having made their First Communion.

In earlier days when the Catholics were

much fewer in number, the priests had been used to instruct the children with

great care and method, and did not admit them to Communion until they knew

their Catechism thoroughly, and had gone through a special course of

preparation. The age for First Communion was then as a rule about fourteen

years. One cannot indeed but be struck with admiration at the exact knowledge

of all that concerns the sacraments which so many of the old Lancashire

Catholics, who were brought up in this system, show, when they come to

confession at the time of a mission.

It was no wonder, then, that there should

be much questioning and opposition amongst many of the clergy when they saw

Father Furniss's new method of preparing, in the short space of a few weeks'

mission, hundreds of children and young persons for Communion who were so

ignorant of Christian doctrine and had not yet perhaps even made their First

Confession, and admitting many to First Communion at a much earlier age than

had been customary; for his practice was to secure the first reception of the

Holy Eucharist, as a general rule, to all the children ten years old, and

frequently even younger, both on account of the risks of their failing to make

their First Communion later, and because he judged that it was more profitable

for them, and more honourable to Our Divine Lord, that they should do so, when they

were yet comparatively innocent, and their hearts unsoiled by habits of

grievous sin.

When, however, it was seen that several

leading priests, who were held in great esteem for their prudence and zeal,

invited him to give Children's Missions in their parishes, and the success and

fruits attending them were manifest, all generally approved of his method, and

many who had most opposed it, became his most ardent supporters and advocates.

——✤——

Method of Father Furniss in

Conducting a

Children's Mission.

ather Furniss, in his separate Children's Missions, was, as a

rule, accompanied by another Father, that is, when one could be spared; but, as

this was often impossible on account of the small number of missioners, he

frequently, and in his last years generally, went alone. The missions, except

in small places, lasted always three weeks. He considered less time than that

quite insufficient to do the work thoroughly. He made a great point of the

mission being well announced by the clergy in the church and throughout the

parish, repeatedly for some weeks beforehand, and of special prayers being said

for its success, that the children might look forward to it with eagerness, and

be all prepared to attend the exercises from the beginning. He also took care

that his little books of hymns and devotions during Mass should be circulated

in good time amongst the children, and that they should be taught in the

schools to sing them, so that all things might be ready for his coming to begin

the mission.

His missions were intended not only for

children who were going to school, or those under fourteen years of age, but

also, and indeed principally, for big boys and girls who were at work, up to

the age of seventeen and eighteen, especially those who had been brought up in

much ignorance and neglect of religion, and perhaps had never been to confession

at all in their lives.

As one Children's Mission was very much

like another, and to give an account of one is to give an account of all, I

will make my own the narrative of one of our Fathers who was a companion of Father

Furniss in several of his Children's Missions, and describe the various

exercises, beginning with the evening service, which was of course the

principal exercise of the day. This began generally at half-past seven. It may

seem to be a late hour for children; but it must be borne in mind that in large

towns the chief part of his evening audience were not school-children, but

working-boys and girls from the age of twelve to sixteen. The church doors were

not opened till six o'clock. Father Furniss took care to be then already in the

church. He would sit on the mission platform watching the children coming in,

or be putting them in their places, keeping order, and seeing that they behaved

well. This he considered very important, not only that these rough

half-civilised children might be taught how to behave in the church, but also

in the interest of his Children's Missions; since a great objection had been

made against them in some quarters, on the plea that it was impossible to bring

so many children together without causing noise, confusion, and bad behaviour.

Father Furniss wished to show that this objection had no real foundation in

fact; and that it was quite possible to bring the largest number together and,

at the same time, to have perfect order. Hence he always took the greatest

pains to prevent any sort of disorder and confusion; and in this he succeeded

admirably, especially by being himself in the church as soon as the doors were

opened, to see that all came in quietly and orderly, and to suppress at once

any noise or disturbance that might arise.

He strongly condemned the practice of

keeping the doors closed till a short time before the service began. He said

that if the children assembled at the church-doors in large numbers, and then

made a rush into the church, then such noise and confusion would ensue that it

would be impossible to restore order, and they would be in a state of disquiet

all through the service. Whereas, if they dribbled in slowly, a few at a time,

during an hour or an hour-and-a-half, they would find on entering the church an

atmosphere of quiet and order, which it would be easy to maintain throughout

the evening. During this time, as he was seated on the platform, he would

sometimes speak quietly to the children, asking them questions about

themselves, especially when they were poor, little, and wretched-looking; for

such children were the special object of his care and love. At other times he

would give some short simple instructions, in a half voice, to those near the

platform. Thus in one way or other he kept himself and the children busy during

the hour or hour-and-a-half they were coming in. He felt, of course, this

waiting a wearisome and painful duty, but in the long run it fully repaid him,

and bore abundant fruits.

When a sufficient number of children were

assembled, that is, when the church began to fill, he would start the singing

of a hymn. This had a two-fold effect—first, it kept the children occupied, and

let off the steam, which otherwise would have evaporated in noise and talking;

and, secondly, it taught the children to sing properly, which in view of the

Children's Mass and other mission services he thought of the greatest

importance.

I may here say a few words about his way of

teaching these poor rude uncultured children to sing. Near the platform he would

generally have two or three benches of boys, and the same number of girls on

the opposite side—of course the sexes were always separated at all the mission

services,—who had practised the mission hymns for some time before at school.

These led the rest. All who could read had their little hymn-books, and soon

caught the tunes, so that after a few days they sang the hymns fairly well. He

would not allow difficult and fantastic airs. He had his own, which he

generally wished the children to sing. They were pious and easy tunes, which he

had picked up here and there in his missions. Most of them are to be found in

his Sunday School book. He adopted

various plans for the singing in his missions, according to circumstances. If

he found that both boys and girls sang well, he would have them sing

alternately. If the boys could not sing well enough to sing alone, he would

make the boys and girls sing together. Sometimes the boys sang so badly that he

had to suppress them entirely, at least during the earlier part of the mission,

and the girls sang alone; but this was a rare case, and he did not like it.

He was very much opposed to the singing

being confined to the school-children alone, but would encourage all to join in,

and, as the tunes were easy, this was not difficult; so that, as the mission

went on, the singing became more general; in fact, one might say that all the

children sang; and he took great pains to make them sing well. Though no

musician himself, he had a sufficiently correct ear to know when the singing

went wrong. He would not allow the children to sing out of tune, too quickly,

or not in proper time; all this he regulated himself, and succeeded admirably.

His aim being to make the children sing devoutly and quietly, he was severe

with boys with loud rough voices who shouted and bellowed; though he was

equally severe on big girls with fine voices who sought particularly to

distinguish themselves. He wished the singing to be congregational and not

individual.

This practising of hymns, with intervals,

would last more or less half-an-hour, at the end of which time pretty well all

the children he expected would be in the church. He was very averse to begin

the service before all were assembled, as a number of children coming in late,

and not knowing where to find a place, will often cause noise, and be a

distraction to others.

The

Beginning of the Service.—As soon as the children were all assembled, and

fairly tired by the singing, and, having thus let off the steam, were brought

to a state of quiet and calm, he would bid them all kneel down; then together

with the children he made slowly and solemnly the Sign of the Cross. The children generally sang the words; otherwise

they said them all together in the same tone with a loud voice. This would be

followed by singing or saying in the same way the Good Intention. Then would follow one Decade of the Rosary. He varied his way of saying this decade. Sometimes

he would make the children sing it in a monotone, slowly and solemnly, the

girls singing the first half, the boys the second. Sometimes they would all

sing it together. At other times they would all say it together, or boys and girls alternately, but always very

slowly and reverently, and with pauses, a few words only at once. He generally

gave out a special intention for every Hail Mary. These intentions bore on what

was practical for the mission, and varied each evening. When the Rosary was

finished, he made them all sit down.

Next would follow:—

The Notices.—He

considered these of the greatest importance. He took great pains over them, and

showed great art in their selection, and in his way of giving them out. He had

a great number of them—repeating most of them night after night all through the

mission. This might appear useless to some, but he would answer the objection

by saying that every night brought new comers, and further, that many children

were so dull, or so inattentive, that it was only by ceaseless repetition he

made himself understood.

His mission notices, moreover, might be

divided into general and special: general,

which regarded the mission generally, as, v.g.,

the hours of service, that children should be in good time, that they should go

straight home and quietly on leaving the church, together with two other

notices: first, the promise of a medal to those children who should bring a

child to the mission, that was not attending; and secondly, that if they knew

of any Catholic child that had not been baptised, they should come and tell the

missioner, and that if any Catholic child then in the church had not been